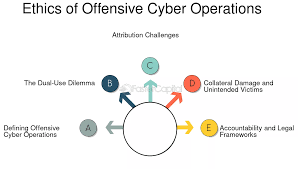

Ethical dilemmas in offensive cybersecurity operations is a complex and critical topic that explores the moral and ethical considerations that arise when organizations, governments, or individuals conduct offensive actions in cyberspace. Offensive cybersecurity refers to proactive measures taken to identify, exploit, or neutralize cyber threats, often before they can harm a system or organization. While offensive operations can help protect digital assets and prevent cyberattacks, they also raise questions about legality, proportionality, privacy, accountability, and the potential for unintended consequences.

Let’s break down the ethical dilemmas involved in offensive cybersecurity operations, including real-world scenarios and frameworks to navigate these challenges.

Offensive cybersecurity involves actively engaging in actions to disrupt, deceive, or neutralize potential or ongoing cyberattacks against a network or digital infrastructure. This could include activities such as:

Hacking back: Launching counterattacks to disrupt or disable attackers' infrastructure.

Exploitation: Finding vulnerabilities in a system and using them to gain access or control, often to mitigate an emerging threat.

Deception: Creating false data or fake systems to mislead attackers and divert their efforts.

Cyber Espionage: Accessing a foreign system to gather intelligence or preemptively disable a threat.

Denial of Service (DoS): Intentionally disrupting the operations of a malicious actor or their infrastructure.

These actions are typically carried out to prevent more severe cyberattacks or to retaliate against adversaries in the cyber domain. However, offensive cybersecurity operations raise a number of ethical challenges.

Legality: Offensive actions like hacking back or exploiting vulnerabilities may be illegal, depending on the country’s laws. For example, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) in the U.S. prohibits unauthorized access to computer systems, which could make retaliation against attackers illegal.

Morality: While hacking back or exploiting vulnerabilities may seem justified to stop an attack, such actions could harm innocent parties, such as disrupting critical services or damaging third-party systems. The ethical dilemma is whether the potential benefits of stopping an attacker outweigh the harm to unintended targets.

Disproportionate Response: Offensive operations must be carefully calibrated to avoid escalating conflicts. An attack that disrupts an attacker’s entire network might cause unnecessary harm to third parties, especially if the attack is broader than initially intended.

Collateral Damage: When an offensive operation is executed, there is always a risk of collateral damage to innocent individuals or organizations. For example, a nation-state may launch an attack against a cybercriminal group, but their operations could affect businesses or individuals unrelated to the criminal activity.

Escalation: Offensive operations could escalate conflicts between states or organizations, leading to greater damage or unintended consequences. The challenge is to determine when a response is justified and when restraint is needed.

Invasion of Privacy: Offensive actions often involve collecting data, monitoring systems, or intercepting communications. While these operations may be aimed at defending against cyber threats, they risk violating the privacy rights of individuals or organizations that are not directly involved in the attack.

Surveillance: Offensive cybersecurity operations, especially those that involve espionage or intelligence gathering, could infringe on the privacy of individuals or entities that are not the target of the operation. This becomes particularly controversial when such surveillance is conducted on citizens or organizations without their knowledge or consent.

Attribution: Determining who is responsible for a cyberattack is often challenging. False attribution can lead to misdirected offensive actions, including attacks on innocent or unrelated parties. Cyberattacks are designed to be stealthy, making it difficult to definitively identify the perpetrator.

Accountability: In the event of a wrongful or malicious operation, there must be clear lines of accountability. Who should be held responsible when offensive operations go awry? Governments, private organizations, or individual hackers may all have a stake in such decisions.

Ethical Hacking: In offensive cybersecurity, ethical hacking is performed with explicit consent to identify vulnerabilities and fix them before attackers exploit them. The ethical dilemma arises when ethical hackers step over the line into unauthorized actions that may harm systems or individuals in the process of defense.

Malicious Hacking: The line between ethical and malicious hacking can sometimes blur, especially when the intent behind the operation is unclear. Offensive actions intended to stop one adversary could inadvertently lead to harmful activities that are morally or legally questionable.

In navigating these ethical dilemmas, various ethical frameworks and guidelines can help guide decision-making:

The utilitarian approach seeks the greatest good for the greatest number. Under this framework, an offensive cybersecurity operation would be considered ethical if it maximized the overall benefits (e.g., preventing widespread harm) while minimizing harm to individuals or third parties.

Challenges: The difficulty lies in quantifying the potential benefits versus the harm. What if an operation causes more collateral damage than initially anticipated? Can the overall benefit truly justify the harm done?

Deontological ethics is based on the belief that actions are morally right or wrong regardless of their outcomes. A deontologist might argue that offensive operations such as hacking back are inherently wrong, regardless of the potential benefits, because they involve illegal or unethical behavior.

Challenges: This approach can be overly rigid and doesn’t take into account the complexities or nuances of each individual situation. For example, some would argue that hacking back is justified if it prevents a much larger-scale attack on critical infrastructure.

Just War Theory is a framework that originated in the context of warfare but can be applied to cybersecurity. According to this theory, an offensive action is ethical if it meets the following criteria:

Just cause: The offensive action is in response to an ongoing or imminent attack.

Legitimate authority: The action is authorized by a recognized authority, such as a government or military force.

Proportionality: The offensive action must be proportional to the threat posed.

Last resort: The operation should only be conducted when all other means of defense (e.g., diplomatic measures or defensive cybersecurity actions) have been exhausted.

Challenges: Applying these principles to cybersecurity can be difficult due to the ambiguous nature of cyber conflicts and the lack of a universally accepted framework for cybersecurity warfare.

Virtue ethics focuses on the moral character of the individual performing the action rather than the action itself. A virtuous cybersecurity operator would be someone who demonstrates qualities like integrity, restraint, and responsibility. From this perspective, the ethical focus would be on the motivation and intent behind the operation.

Challenges: This approach can be difficult to apply universally, as different people and cultures may have different views on what constitutes a “virtuous” act.

Many nation-states engage in offensive cybersecurity operations as part of their national security strategy. For instance, a state may launch a cyberattack on a hostile nation’s critical infrastructure to prevent an imminent physical attack. The ethical dilemma arises if the attack causes unintended harm to civilians or disrupts essential services (e.g., hospitals or financial systems).

Corporations may engage in offensive cybersecurity operations to defend against competitors or cybercriminals. For instance, a company may hack back against a competitor suspected of cyber espionage. While defending corporate assets is important, such actions could cross legal boundaries and result in serious ethical and legal consequences.

Ransomware attacks are a growing threat, with cybercriminals demanding payments to restore critical systems. In response, some entities may consider offensive operations, such as disabling the attacker’s infrastructure or recovering the stolen data. However, these actions must be carefully balanced to avoid creating more chaos or impacting innocent parties.

Ethical dilemmas in offensive cybersecurity operations underscore the need for clear frameworks and guidelines to navigate the complexities of the digital landscape. Balancing the effectiveness of offensive actions with the moral and legal boundaries that govern them is crucial for both organizations and nation-states.

Ultimately, any offensive operation in cybersecurity must be undertaken with careful consideration of its potential risks, collateral damage, and legal ramifications. While the end goal is to protect individuals and organizations, it is equally important to ensure that the methods used are ethically sound and do not create greater harm.

Would you like to:

🧑💻 Explore real-world case studies of offensive cybersecurity operations?

🔒 Discuss legal implications of offensive actions in different jurisdictions?

🧠 Dive deeper into ethical frameworks applied to cybersecurity?

Let me know what you'd like to explore next!

#trending #latest

Explore the Duolingo English Test for Indian Students Abroad... Read More.

Simple Steps to Get Your Canada Student Visa in 2025... Read More.

Fake posts hit Czech PM Fiala's X

Fake posts hit Czech PM Fiala's X

Fake posts disrupt Czech PM Fiala's X account security

Switzerland Tightens Export Rules

Switzerland Tightens Export Rules

Switzerland expands export controls on dual-use goods

Google unveils Ironwood AI chip

Google unveils Ironwood AI chip

Google introduces Ironwood chip to accelerate AI tasks & apps

TSMC Q1 revenue up 42%

TSMC Q1 revenue up 42%

TSMC sees 42% revenue surge in Q1, surpassing forecasts

Google unveils Ironwood AI chip

Google unveils Ironwood AI chip

Google's Ironwood chip boosts AI processing and app speed

Amazon CEO Outlines AI Vision

Amazon CEO Outlines AI Vision

Amazon CEO reveals AI investment plans in new letter

Osaka Hosts World Expo 2025

Osaka Hosts World Expo 2025

Japan blends tech and culture at Osaka Expo 2025 launch

© MyEduGoal. All Rights Reserved. Design by markaziasolutions.com